Ottawa – In 2024, the Government of Canada published the updated Draft State of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Report, which proposes to conclude that the class of PFAS, excluding fluoropolymers as defined in the updated draft report, may cause harm to human health and the environment.

A class-based approach for PFAS is appropriate, given:

- The Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) defines a class of substances as any two or more substances that contain the same portion of chemical structure; have similar physical-chemical or toxicological properties; or have similar types of use. Substances included under the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) definition of PFAS meet the definition of class under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, as they contain the same portion of chemical structure.

- PFAS have many properties, including oil and water repellency, which has led to their widespread use and extreme persistence in the environment.

- The increasing body of scientific evidence suggesting that concerns for human health and the environment for well-studied PFAS are broadly applicable to other PFAS.

- The scientific expectation is that combined exposures to multiple PFAS will increase the likelihood of detrimental impacts.

- A class approach can help prevent the substitution of one regulated PFAS for an unregulated PFAS that potentially possesses similar hazardous properties.

As part of the Revised Risk Management Scope, the Government of Canada is proposing activities to reduce environmental and human exposure to PFAS through a phased approach, which includes:

- as a first step, a regulation under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, to restrict PFAS not currently regulated in firefighting foams

- additional instruments under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 to prohibit PFAS in other uses or sectors

- possible voluntary risk-management actions to achieve early results to reduce releases of the class of PFAS.

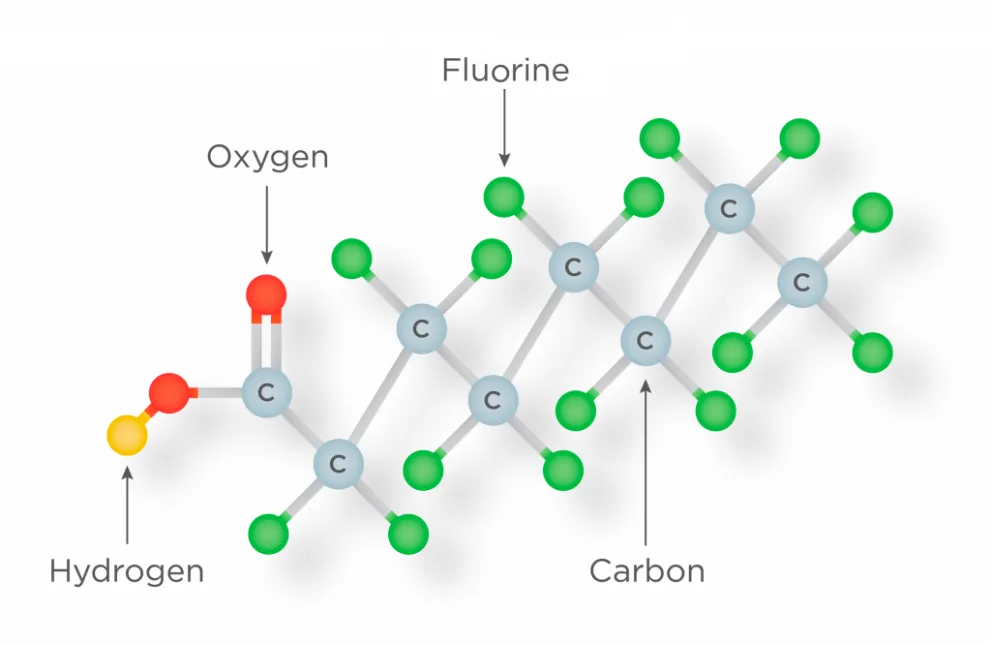

The updated Draft State of PFAS Report uses the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s 2021 definition for PFAS: fluorinated substances that contain at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom (without any H/Cl/Br/I atom attached to it); that is, with a few noted exceptions, any chemical with at least a perfluorinated methyl group (–CF3) or a perfluorinated methylene group (–CF2–) is a PFAS.

Fluoropolymers

Fluoropolymers are a group of polymeric PFAS and are defined in the updated Draft State of PFAS Report.

Based on available information, fluoropolymers may have different exposure and hazard profiles compared with other PFAS. Given these differences, additional work on fluoropolymers is warranted, and they will be considered in a separate assessment. The Ministers will also consider at a future date whether fluoropolymers are possible candidates to the Watch List under section 75.1 of CEPA. Canadians will be consulted on the process for additions to the Watch List in the near future.

PFAS in Canada

PFAS are a class of thousands of human-made substances and are found nearly everywhere in the environment, including in the air, groundwater, oceans, lakes, rivers, and soils, as well as in wastewater, landfill leachate, and sewage sludge worldwide. Certain PFAS have been detected in humans and wildlife globally, and a range of health effects have been reported for well-studied PFAS.

Canada has not waited for this updated report to act. Following assessment activities completed in 2006 and 2012, the manufacture, use, sale, offer for sale, and import of three subgroups of PFAS (PFOS, PFOA, and LC-PFCAs) have been prohibited in Canada, with limited exemptions, through the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2012. Proposed Regulations that would repeal and replace the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2012, were also published in May 2022, which propose to further restrict these PFAS by removing or providing time limits for most remaining exemptions. The publication of the final Regulations is expected to take place in the fall of 2024 and would come into force six months later.

The New Substances Notification Regulations (Chemicals and Polymers) regime in the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 sets out information to be submitted for new substances (that are not on the Domestic Substances List). When the new substances meet regulatory thresholds, they must be reported to the Government before they are imported into or manufactured in Canada. This allows the Government to assess them for potential risks to human health and the environment and, if appropriate, decide to prohibit or impose control measures before they enter Canada. New PFAS proposed for importation into Canada or being manufactured in Canada are assessed under this regime. Approximately 100 of the over 280 PFAS notified to the New Substances program have been subject to risk management actions under CEPA.

The Government is also proposing taking action to protect firefighters and reduce Canadians’ exposure to PFAS in drinking water and has also published an interim standard for PFAS in biosolids. Activities are also being undertaken under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement to reduce releases of these substances into the Great Lakes. In addition, in 2021, Canada nominated long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (LC-PFCAs), their salts, and related compounds to be added to the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. If listed on the Stockholm Convention, this would reinforce domestic regulatory activities. Additionally, it would help global efforts toward the elimination of these harmful substances, further protecting Canadians and the environment. Parties to the Convention would be required to eliminate or restrict the production, use, and trade of LC-PFCAs, while also requiring environmentally sound management of waste containing them.

Ongoing research and monitoring activities are building on available science about the environmental and human exposure levels and impacts of PFAS. This includes biomonitoring of certain PFAS as part of the Canadian Health Measures Survey, surveillance studies of certain PFAS in Arctic and Subarctic locations as part of the Environmental Monitoring and Research subprogram of the Northern Contaminants Program, and other monitoring. The Government is also gathering information from industry to better understand uses and sources of release of PFAS and is considering adding certain PFAS to the National Pollutant Release Inventory.