Ramtin Attar is the CEO and co-founder of Promise Robotics — part of a small group of Canadian companies and researchers working on technology to help homebuilders catch up with innovation in other industries.

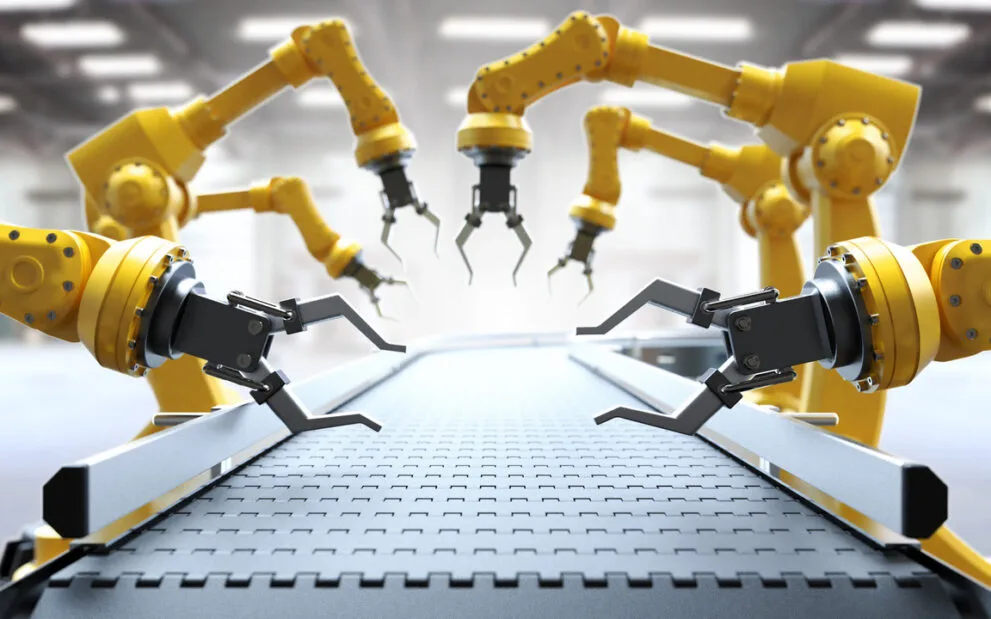

Using artificial intelligence (AI), the arms are reading blueprints and, in a sense, thinking for themselves about what cuts to make, what pieces to nail together and where holes need to be drilled for wires and plumbing.

“So they can sort of on the fly decide what is the tool I need to use, what is the sequence of tasks I need to do,” Attar said.

It’s a pretty radical concept for an industry that experts say needs a serious upgrade in order to confront a shortage of skilled labour and a dire need for new housing during an affordability crisis in Canada.

“There’s a big disparity between the construction industry and the other industries leveraging AI and robotics,” said Daeho Kim, who researches robotic construction as an assistant professor in civil engineering at the University of Toronto.

How the robotic arms work and think

Attar said his company is developing AI for construction to master some of “the physical tasks that previously were really just the domain of a human.”

Instead of creating single-function robots and pre-programming them to do highly specific tasks, Promise Robotics bought “off-the-shelf” robotic arms, began programming its own AI on construction skills and trained the arms to make parts of houses.

Since starting in 2019 and raising $25 million, Attar said the company has created a “foundational brain” that can scan building plans and make decisions about the fastest way to build parts of a house or multi-unit dwelling. Able to adjust and make several different types of walls, floors and roofs, the arms are different from many larger machines in huge factories that make prefabricated homes.

- The next big thing in construction robotics is building big

While Attar is a tech guy who spent years working at Autodesk — which creates software for such industries as engineering, construction and manufacturing — his company’s co-founder, Reza Nasseri, has decades of construction experience and started one of Canada’s largest pre-fab homebuilding companies, Edmonton-based ACQBuilt.

Unlike ACQBuilt’s multimillion-dollar factory, the Promise Robotics system is highly portable and can be set up in warehouse-type spaces anywhere for much less money. That’s attracting a lot of interest from homebuilders, Attar said.

Curious builders crunching numbers

After being completed, the walls, floors and roof are sent to the building site, where it takes about a day for workers to assemble the home, complete with windows, doors and stairs, using a crane.

The company says it can cut the total time it takes to build a house to about five months, which is about half the typical length, according to government data. Attar said the company already has a builder in Edmonton as a client and that more than 20 others from across Canada visited Promise Robotics in 2024, intrigued by the possibility that setting up a temporary facility with robotic arms near their developments could double their production.

Kevin Lee, CEO of the Canadian Home Builders’ Association, said most construction companies are just too small to spend money on developing their own technology, but “robotics, if they can be done in a cost-effective way, start to become very interesting.”

Other advances and robots to come

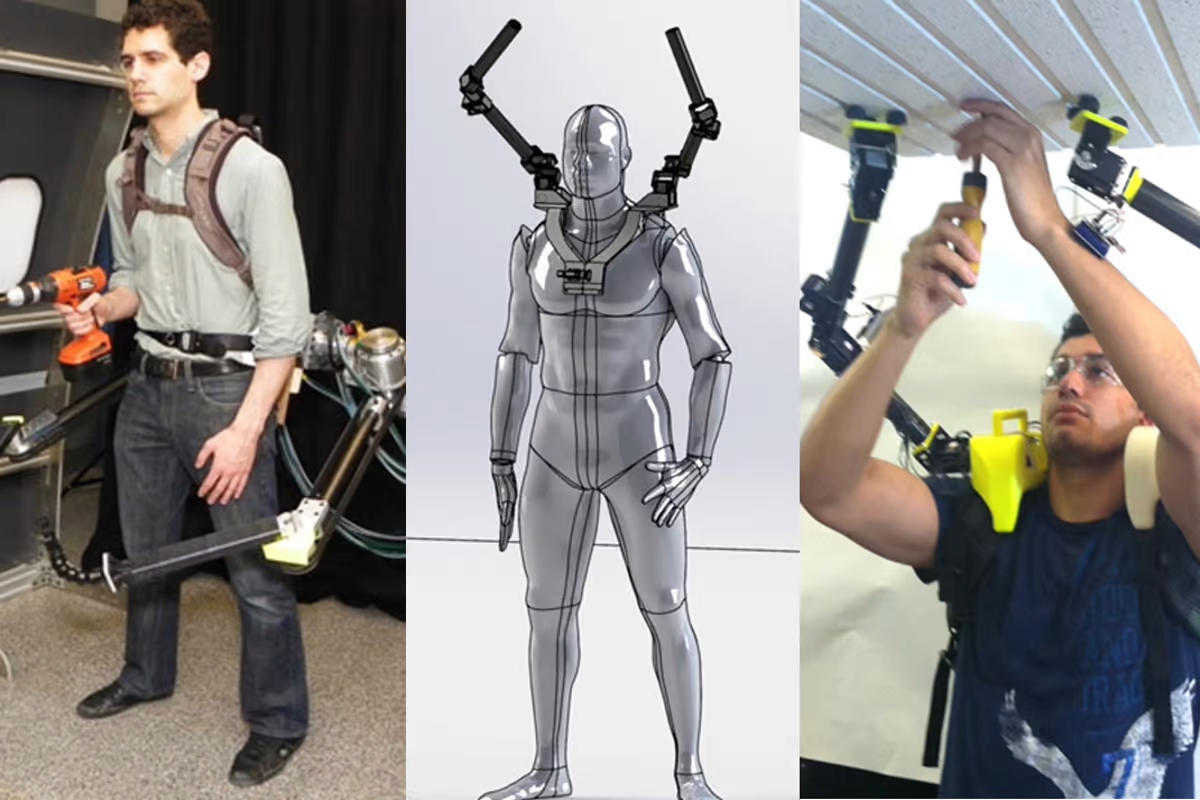

Arms aren’t the only way robots are moving into construction.

At the University of British Columbia’s Smart Structures Lab, civil engineering professor Tony Yang is working on turning conventional cranes, excavators and loaders used in construction today into robots by equipping them with all kinds of sensors and connecting them by a wireless signal to a computer.

On-site tests have already been done with Bird Construction in Richmond, B.C., where cranes and forklifts move heavy materials around guided by AI, not by workers using a remote control.

Yang said the technology is similar to self-driving cars and will be “the next generation robot you will start seeing in the construction sites,” possibly within 10 years.