The human hand is one of the most staggeringly sophisticated and physiologically intricate parts of the body. It has more than 30 muscles, 27 joints alongside a network of ligaments and tendons that give it 27 degrees of freedom. There are more than 17,000 touch receptors and nerve endings in the palm alone. These features allow our hands to perform a dazzling array of highly complex tasks through a broad range of different movements.

But you don’t need to tell any of that to Sarah de Lagarde.

In August 2022, she was on top of the world. She had just climbed Mount Kilimanjaro with her husband and was supremely fit. But just one month later, she found herself lying in a hospital bed, with horrific injuries.

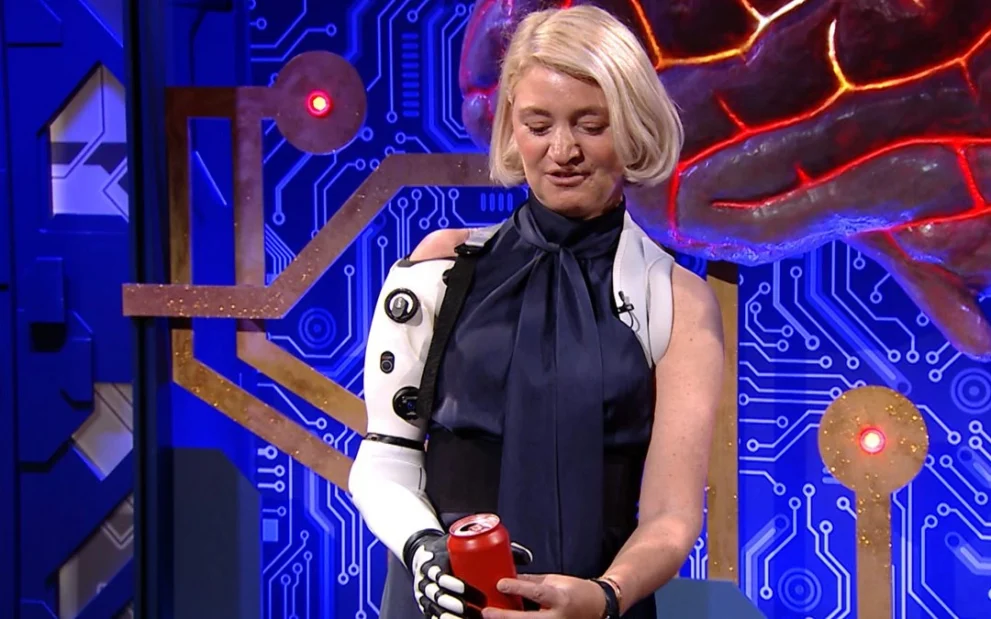

While returning home from work, De Lagarde slipped and fell between a tube train and the platform at High Barnet station in London. Crushed by the departing train and another that then came into the station, she lost her right arm below the shoulder and part of her right leg.

After the long healing process, she was offered a prosthetic arm by the UK’s National Health Service, but it offered her little in terms of normal hand movement. Instead, it seemed to prioritise form over functionality.

“It doesn’t really look like a real arm,” she says. “It was deemed creepy by my children.”

The prosthetic only featured a single joint at the elbow while the hand itself was a static mass on the end. For nine months she struggled to perform the daily tasks she had previously taken for granted, but then was offered something transformational – a battery-powered bionic arm utilising artificial intelligence (AI) to anticipating the movements she wants by detecting tiny electrical signals from her muscles.

“Every time I make a movement it learns,” De Lagarde says. “The machine learns to recognise the patterns and eventually it turns into generative AI, where it starts predicting what my next move is.”

With this level of complexity, it’s no wonder that attempts to match the versatility and dexterity of human hands have evaded medical professionals and engineers alike for centuries. From the rudimentary spring-loaded iron hand of a 16th-Century German knight to the world’s first robotic hand with sensory feedback created in 1960s Yugoslavia, nothing has come close to matching the natural abilities of the human hand. Until now.

Advances in AI are ushering in a generation of machines that are getting close to matching human dexterity. Intelligent prostheses, like the one De Lagarde received, can anticipate and refine movement. Soft-fruit picking bots can pluck a strawberry in a field and place it delicately in a punnet of other berries without squishing them. Vision-guided robots can even carefully extract nuclear waste from reactors. But can they really ever compete with the amazing capabilities of the human hand?